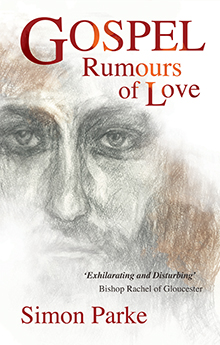

‘Meet Jesus unplugged,’ writes former Fleet Street editor, Richard Addis, after reading my latest novel. ‘In a stunning act of imagination, Simon Parke shatters every stained glass window in your mind.’

I am not the first to try this and will not be the last. But Gospel: Rumours of Love is my attempt to inhabit the familiar gospel narrative which we know so well, yet may not know at all. Weighed down by agreed statements of belief about him, Jesus can become distant, a rather institutionalised figure; and no one lives well in an institution. It is significant that Jesus reserved most of his anger for the religious of his day. He didn’t fit in; I suspect he still doesn’t.

Remarkable and much-loved records exist of his sayings and doings. But there remain hints and clues in the story line which are never pursued; and gaps in the narrative the size of several barn doors. It’s the hints and gaps that historical fiction feeds on. In Gospel: Rumours of Love we visit both familiar and unfamiliar places.

What, for instance, did it feel like for Jesus to leave home, to leave racist Nazareth behind? Or to fall out with his family? Or to wake from savage crucifixion in a dark chill tomb? Were his friends more of a hindrance than a help? How did he feel about events in Bethlehem? Why was he so angry? And why was a woman – whose testimony didn’t count – chosen as the first witness to the resurrection?

Gospel is told in the first-person through the eyes of Jesus (Yeshua), Mary Magdalene (Miriam), and Mary, mother of Jesus; we look at the world through their gaze. And it is a love story; though maybe not the traditional kind, as this reader observed:

‘This beautifully-crafted book will not leave any reader indifferent,’ says Rachel Treweek, Bishop of Gloucester. ‘As Simon Parke seeks to get under the skin of Jesus the man and his early disciples, so this book gets under the reader’s skin. I found it both exhilarating and disturbing as the provocative narrative, shot through with familiar words and stories from the Gospels, took me to places of both comfort and objection. Yet through it all I was profoundly moved by the outrageous love of the frequently-raging Yeshua. This is a poignant and mystical story of love which is likely to raise more questions than answers, but then that is not unlike the stories Jesus himself once told.’

So, in Gospel, we don’t follow Jesus, we are Jesus, living the hot and dangerous landscape through his eyes. No longer is he some doctrinal assertion on legs – but a human, whose feet are hurt by stones in his sandals. And who sometimes just has to get away from his friends.

‘The result is much more than an historical novel,’ wrote one reader, a former headmaster. ‘It is an epic account of Jesus as a human being, a man whose intellectual, physical and spiritual strength lead him into conflict with family and authority. It follows Jesus’ development into a revolutionary – but one who never loses the force of love whatever the pain and provocation.’

As you can imagine, it was not an easy book to write. We’ll think twice before entering the mind of Jesus, for it will not be an easy ride. Here is a disturbing man in dangerous times; here is magnificent courage, frightening intelligence, endless compassion and terrible and unfair suffering. I have to say, nothing quite prepared me for his rage. But then there was much to be angry about: the Pharisees, the Temple authorities, Herod, Rome – really, where to begin? So what was the spirituality inside him that created such resilience in the face of conflict?

Alongside the historical research, I have drawn freely from six of the Gospels: Matthew, Mark, Luke, John, Thomas and Mary Magdalene. But however thorough the research, a novel must always be on the fiction shelves; at best, informed imagination. And at the heart of it all is Jesus’ voice. Finding a voice for Jesus was perhaps the hardest part. Clearly, the Gospels of Matthew, Mark and Luke give him a very different voice to that of John; and Thomas’s take is different again, as is Mary’s. Who can claim the authentic voice of Jesus?

Given that we cannot sit at his feet and listen to him ourselves, we must always listen through the filter of other people’s agendas. This can put a veil between him and us, a strange separation. But whatever and however, I hope in some manner you hear him afresh in Gospel: Rumours of Love. He was a prophet with a huge, if dry, sense of humour.

Karl French is a writer and journalist specialising in cinema and popular culture. He too was kind enough to look at this work and found there, to my relief, ‘a wonderful and profound thing, a book in which the mundane and the miraculous exist comfortably side by side. The book itself sits comfortably alongside – indeed compares favourably to – similar re-imaginings of the life of Christ by Nikos Kazantzakis, Philip Pullman and Colm Tóibín, but it is also a singular and distinctive piece of work, an always compelling, thoughtful and thought-provoking – and at times – a deeply moving novel.’

I hope you will forgive my use of others to help me to describe this book, but I find the process difficult. A dancer cannot explain their dance and I struggle to explain my novel. I’ve known Jesus a while and some things cannot be put into words. All I can say is, ‘Behold the man. And behold the women. From here on, they are yours and not mine.’